In the song Subterranean Homesick Blues, Bob Dylan rasped (some say rapped) “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”. That’s true enough, but you might want one to tell you why it blows the way it does, and that’s what I’m going to attempt here. You may recall from the last post a discussion of climate indices and their interactions on influencing weather in the tropics. We will divert our focus poleward here and talk about the relationships between climate indices and the weather in the mid-latitudes, or the regions of the world where many of the key global crops are grown. We will start with the jet stream, a constantly moving river of air some 4-7 miles above the earth’s surface. The jet stream is a manifestation of the ‘battleground” where cold/dry polar air meets warm/moist tropical air in a Sisyphean attempt to equalize the temperature contrast between the equator and the poles.

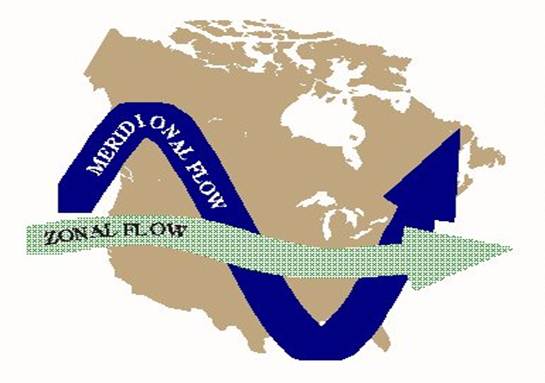

As a crude approximation, the jet stream flow is described as being either zonal or meridional. Zonal flow (see picture) is predominantly west-to-east flow and is often called “flat” flow. It methodically marches the energy of the jet stream and its attendant storms at a regular pace, and thus brings alternating periods of storminess and clear weather. A common feature of zonal flow is that no one particular aspect of the weather remains static in one place over an extended period of time, avoiding the extremes that often plague agricultural production. By contrast, meridional flow (also see picture) has a more pronounced north to south component of the flow, and is often associated with persistent blocking of the jet stream flow, resulting in strong ridges of high pressure and deep troughs of low pressure. These patterns may also be transitory and when they are they result in wild swings of weather or they may become stationary, and unleash a period of persistent weather….be it drought, floods, heat waves or cold snaps. This type of pattern, a persistent meridional flow, are the enemies of crops in the mid-latitudes, most recently as evidenced by the US Midwest drought of 2012.

So, the goal is to look for patterns in the myriad of global climate indices….in sea-surface temperatures , global circulation patterns, solar outputs….for clues as to the predictability of zonal (more crop friendly) and meridional (more crop unfriendly) flow regimes. And there are a few suggestions to be found there. In the last post we discussed the role the PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation), its 20/60 year periodicities and how it has shifted to negative PDO (see below).

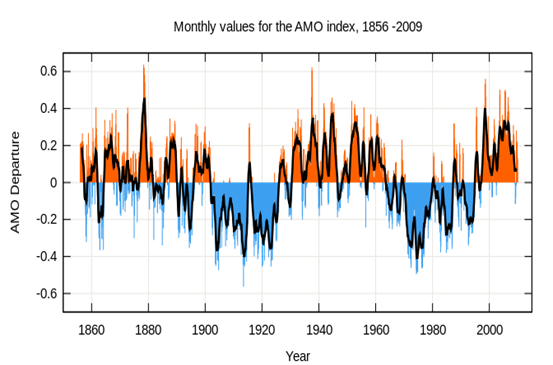

To that, we will add the AMO (yes, the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation, not to be outdone). The predominant periodicity of the AMO, shown above, is 60-80 years. Before we get too carried away, keep in mind we are working with limited datasets and our understanding of these indices is incomplete. Nonetheless, a review of the charts below show that during periods of negative PDO and positive AMO ( for instance the mid 1930’s, the 1950’s and the last few years) were periods when significant disruptions to climate and food production occurred globally and especially in the US.

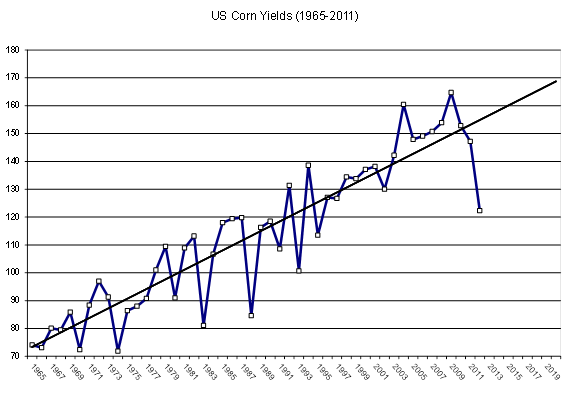

We these days find ourselves bombarded with popular press stories about runaway warming and tipping points in climate, yet a chart of US corn yield deviation from trend shows that the frequency of highly variable yields was greater in the period around the 1970’s than in the 1990’s, punctuated by the drought of 2012. So, the working hypothesis here is that the period of generally benign weather for mid-latitude agriculture has come to an end as the climate system shifts gears and in doing so will promote on average a greater frequency of meridional flow, resulting in droughts, floods, heat waves and cold snaps. Embedded in that last statement is the length of the growing season, which has slowly been increasing and providing very favorable conditions for agriculture…all under an extended regime of zonal flow. Meridional flow will also increase the possibility of early and late frosts, and begin to take away those extra growing season days gained over the last few decades.

Since 2010, a major crop failure has hit in three different regions of the world every year. In 2010, it was a phenomenal drought over Kazakhstan/Ukraine and neighboring areas. In 2011, it was Argentina and southern Brazil (note that weather disruptions in SA prior to the late 1990’s would not have impacted global food production significantly, yet now it will, another new wild card). And this year, the US Midwest. Despite that, this is not meant to predict a disaster every year, that is not consistent with the historical record. But they will become more frequent, and the volatility in global commodity markets will continue. Now more than ever, risk management expertise and discipline will be required. Are you and your organization prepared?